The push for Indigenous history visibility stretches across north central Florida — a conversation sparked by a community-wide lack of awareness.

Alachua County is heavily influenced by its Indigenous history — particularly the Potano, Timucua and Alachua Seminole tribes. Despite this centuries-old legacy, the history and contributions of these Indigenous groups remain relatively unknown.

November marks Native American Heritage Month and is an opportunity to celebrate Indigneous people, their histories and contributions.

In celebration of Native American Heritage Month, local residents and academics are making efforts to highlight this rich Indigenous history and encourage education of Indigenous peoples’ contributions to our community.

Nicole Nesberg, an adjunct history professor at Santa Fe College and member of the Sault Tribe of Chippewa Indians — an Indigenous group clustered in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula — is one Alachua County resident leading the charge for community awareness.

“We are starting to backtrack where we’ve gone through Florida history and remembering the African American history that is here,” Nesberg said. “Now, we are doing the next step where we are remembering the Indigneous history that is here.”

The history of Indigenous groups and UF are also intertwined, as the university itself is built on Indigenous land. Thus, the campus contains several documented sites with archaeological remains affiliated with Native American tribes.

These sites include the Levin School of Law, the eastern margin of Graham Woods and areas south of the intersection of Archer Road and Southwest 13th Street and east of UF Health Shands Hospital, according to an April report by the presidential task force on African American and Native American history.

Remembering and representing forgotten history is a process, she said. But Alachua County communities are slowly accounting for the histories of Native people in Florida.

Organizations across Gainesville have already begun this process through educational events centered around sharing the county’s Indigenous history.

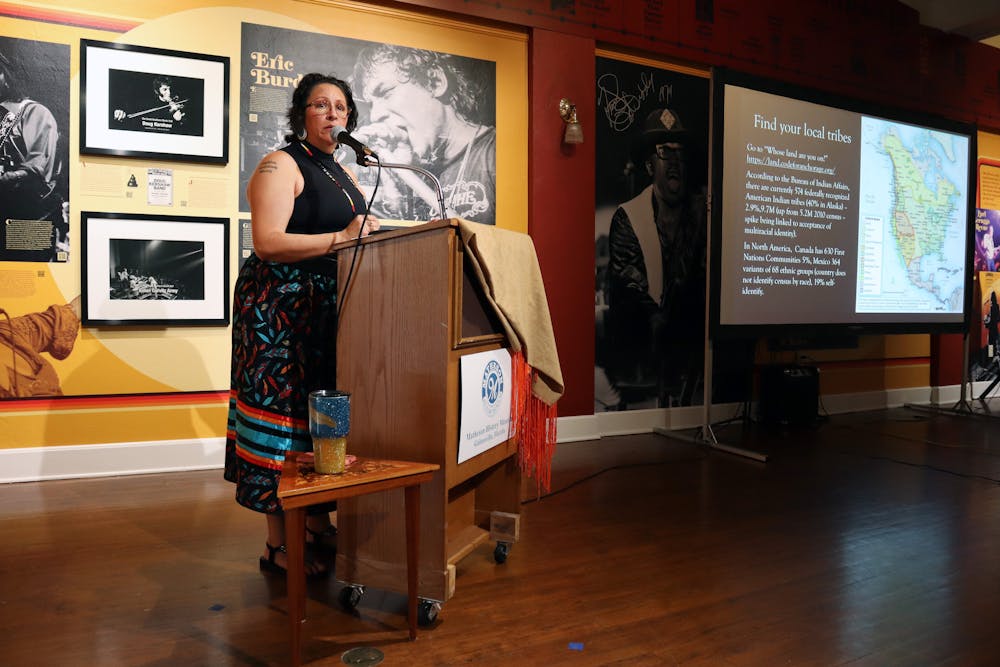

The Matheson History Museum hosted a lecture presentation Nov. 13 led by Nesberg — drawing a crowd of around 30 local residents.

Nesberg’s presentation discussed the lives of the Potano, Timucua and Alachua Seminole tribes, focusing on the impact of their interactions with the various European colonial powers that later colonized north central Florida. Using artwork, statistics, maps and archaeology, she educated audiences on Indigenous history and its persisting impact on modern-day Alachua County.

There are several reasons why Indigenous history has been underrepresented, Nesberg said. They include a trend of history being rewritten to position colonial powers as the discoverers of Indigenous lands, as well as there being a relatively small existing Indigenous population in Alachua County, she said.

“[After] The Seminole War, there were hardly any Indigneous living here,” Nesberg said. “You forget the history of a people once you push them off their land and rewrite history as you being the survivors and the real first people to get here.”

People can honor Indigenous communities through acts of intentional remembrance, Nesberg said. That can be as simple as considering the origins of the ingredients in the food we eat, such as the three sister crops — corn, beans and squash, she said.

Another way Nesberg suggested the community emphasize the influential contributions of Indigenous people is by placing informational plaques at historically Indigenous sites across Alachua County. For example, San Felasco Hammock Preserve State Park, a series of nature trails in northwest Gainesville, traces its origins to the Potano tribe.

Names of community locations can also be changed to commemorate their Timucua and Seminole language origins, Nesberg said — for instance, permanently renaming Lake George, a lake located on the St. Johns River, to Lake Welaka.

If people are exposed to these changes, Nesberg said, they will become curious about the historical origins of places and names in the community, then take on the responsibility of educating themselves.

“It changes your perspective when you remember there were people here for hundreds of thousands of years,” she said.

Liz Hauck, a 37-year-old Alachua County resident, is one of several whose own understanding of her hometown’s Indigenous history was altered by Nesberg’s presentation.

Hauck occasionally attends events hosted by the Matheson History Museum, she said, and found the Native American Heritage Month event insightful — especially in gaining an awareness of the tribes like the Potano.

“I feel I learned a lot about the Indigenous people who populated this land before colonizers and settlers arrived,” she said. “I did not know a lot about the history before the Alachua Seminoles.”

Displays that represent the Potano, Timucua and Alachua Seminole tribes are available at the Matheson, said Kaitlyn Hof-Mahoney, the museum’s executive director. However, Nesberg’s lecture offered a more accessible, interactive opportunity for visitors to learn about Indigenous history.

The museum’s exhibits about Indigenous culture prompted the community’s desire for education, Hof-Mahoney said. Follow-up surveys given to visitors after observing the exhibits and programs, she said, revealed several requests to learn more about Gainesville’s local Indigenous history.

After attending Nesberberg’s presentation, Hauck said, she planned to use her newfound knowledge to educate others.

“I am going to take this knowledge home to my children,” she said. “Make sure they honor and understand the generations of people that came before us and some of the loss and trauma that informed that history.”

Kali Blount, a 66-year-old Gainesville resident who also attended the Matheson event, arrived with a preexisting interest in Indigenous history and its overlap with the history of African runaway slaves.

Blount appreciated that Nesberg discussed the relationship between Indigenous groups and African enslaved people in her lecture presentation, he said, as well as their rebellions against European colonial powers.

“To respect and reveal resistance is really important,” Blount said. “It is our humanity.”

Kenneth Sassaman, a UF archeology professor who contributed research to the UF Presidential Task Force on African American and Native American history and the University of Florida, said he believes Indigenous history is underrepresented in UF curriculum due to the university’s limited Indigenous student population. In Fall 2020, 0.14% of UF’s undergraduate class was American Indian or Alaska Native, according to a report by UF Institutional Planning and Research.

“If we were at the University of Oklahoma, there would be dozens of classes every semester on Native American culture because they have a large contingency of Native American faculty and students,” Sassaman said. “We just don’t.”

In order to encourage UF to create a Native American studies program, there needs to be a push from Native American students on campus, Sassaman said. If this demographic petitioned for the program, it might grab the attention of university administration, he said.

“The president might notice, the provost might notice and [they] might say ‘This is a good idea. Let's do that,’” he said.

Due to the low population of Native American students, Sassaman said, he believes people that aren’t of Native ancestry — such as himself — can still do their part to educate others on Indigenous history.

Next November, he said, he hopes to plan an event with other faculty interested in Native American studies to showcase Indigenous culture through music, food, dance and more.

“Once you build an interest and intensity, maybe you can create some programs that will last and grow,” Sassaman said.

Contact Naomi at nvolcy@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @volcyn_.

Naomi Volcy is a third-year journalism major and the university general assignment reporter for The Alligator. Previously, she was an Avenue staff writer. In her spare time, she enjoys reading mangas, listening to R&B or Indie Rock and dressing up.