While biology may not sound like a creepy affair, some UF researchers are closely studying bizarre diseases that rot amphibians’ skin, along with a new species of worm-like creatures and lizards that eat other animals and their eggs.

Arik Hartmann, a graduate student studying under Ana Longo in UF’s biology department, works with frogs, salamanders and other amphibians.

Hartmann currently studies disease outbreaks in amphibians. He measures outbreaks of sickness, like the fungal infection Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (BD) which causes animals’ skin to rot and fall off.

“It looks really, really gross,” Hartmann said. “I've encountered animals whose faces are rotting off, or their limbs are hemorrhaged, and I'm like ‘they're not long for the world.’”

Hartmann said some people don’t realize amphibians’ importance. They’re what’s known as an indicator species, which means they play an important role in allowing ecologists to measure the health of an ecosystem.

“Even if someone doesn't care about the frogs or the salamanders in the system, amphibians are waving the flag around like, ‘we're not doing okay, this whole system is not doing okay,’ and that has ripple effects throughout every sort of level of organization and ecology,” Hartmann said.

Sarah McGrath-Blaser, a 30-year-old graduate student working in the same lab as Hartman, also studies disease in amphibians.

While on a trip to the Bornean rainforest in 2017, McGrath-Blaser collected two samples of a possible new species of caecilian, a legless, worm-like class of amphibians native to most tropical climates.

After five years, McGrath-Blaser is still gathering data.

“Not that much genetic data exists for them,” McGrath-Blaser said. “We're doing all the work to try to dig up as much of the information as we can to do the comparison so that we can say for sure whether they're a new species or not.”

Jaguars are also misconceived as scary animals. A jaguar’s jaws can crush through the back of its prey's skull at a force of almost 1500 pounds per square inch, according to Field and Stream. Proportionally, it’s the strongest bite of any big cat, stronger than both a lion and a tiger.

To Matt Hallett, a 39-year-old professor in UF’s wildlife ecology and conservation department, a powerful jaguar is just another day at work. Both of Hallett’s graduate degrees involved specifically jaguar research. He travels to Guyana in the spring and summer and teaches at UF in the fall.

Hallett studies animals in the rainforests of Guyana, a country in northern South America. It’s 36% rainforest, and hosts animals like tapirs, piranhas, and of course, jaguars.

“Jaguars are that thing that [goes] bump in the night for a lot of people in Guyana,” Hallett said. “They start to hear noises outside — a dog barking or cows coming close or pig squealing. And it could be because there's a very large, very able predator that's outside and is helping themselves to some of your livestock.”

A large part of his research involved human-jaguar relationships. Farmers often lose livestock to jaguars hunting on the forest’s periphery, but sometimes people blame jaguars for livestock deaths that have nothing to do with them, like drought or disease.

“Our groups try to understand the human side of how people perceive these things, and how they react,” Hallett said. “We're just right now scratching the surface to try to talk to people about how to sort of address the misconceptions, but in a positive way.”

Invasive species can also prove to be ‘scary’ when they are introduced to non-native environments, sometimes having devastating impacts.

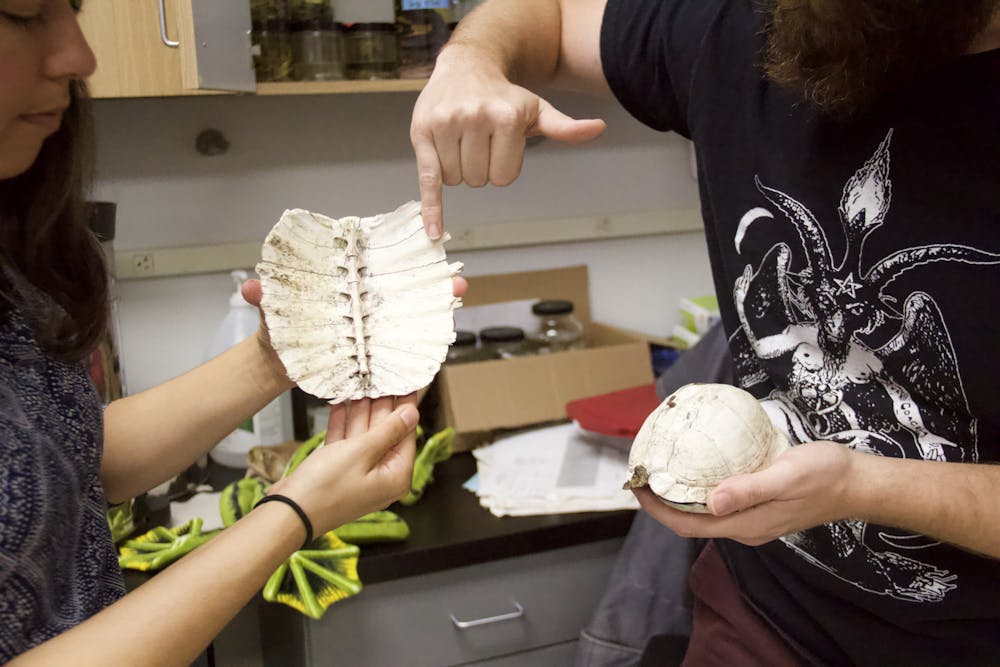

Keara Clancy, a 24-year-old candidate for a master’s degree in wildlife ecology and conservation, studies tegus, a lizard species invading the Everglades that can grow up to four feet.

Clancy currently analyzes and collects data on the tegu’s possible impact on the Everglades. The tegu has a tendency to eat other animals and their eggs, which can be a problem for endangered species like the gopher tortoise, Clancy said.

Clancy is also involved with the Natural Resources Diversity Initiative, a UF student organization that works to involve underprivileged groups in science. Clancy sometimes goes to Gainesville community centers to teach kids about animals, bringing live alligators and snakes to help generate interest in science.

“Obviously [the animals] can be dangerous, but under a professional handling of them, [the children] learn that you can interact with them and learn a lot about them, and they're actually pretty cool,” Clancy said. “They’re basically real-life dinosaurs.”

Clancy tries to teach people reptiles are important, with a prominent environmental impact. She wants to emphasize their influence on ecological systems, even though some people are afraid of them, Clancy said.

“A lot of people have this instinctual fear of reptiles and because of it we kill them, we hurt them, we banish them from our properties, but these are animals that play such an important role in our ecosystem,” Clancy said. “If we learn to start coexisting with them I think that we would be a lot better off.”

Contact Max at mtaylor@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @MTaylor_Journ

Max is a first year journalism major. In the past, she worked as the Editor-in-Chief of her high school's yearbook, and she is now a News Desk Assistant for The Alligator. When she isn't reporting, Max enjoys reading and rock music.