Officer Doug Williams walks through the grass to the tune of middle school boys shouting.

Lined up in rows of seven or so, the boys stand straight. A man stands a few paces away. “Lock it up!” he says.

The boys echo his command, straightening their arms and snapping their fists out in front of them.

They begin to count.

“One, sir!” shouts the short boy, no more than 12, in the front, far left row. He snaps his fist to his side.

“Two, sir!” yells the next in line.

“Three, sir!” “Four, sir!” “Five, sir!” “Six, sir!”

Williams stands a few yards away, watching the boys count off.

This is how employees take attendance here in the middle school sector of the Reichert House Youth Academy, a nonprofit organization supported by the Gainesville Police Department and other local groups, that serves more than 130 at-risk boys in grades five through 12.

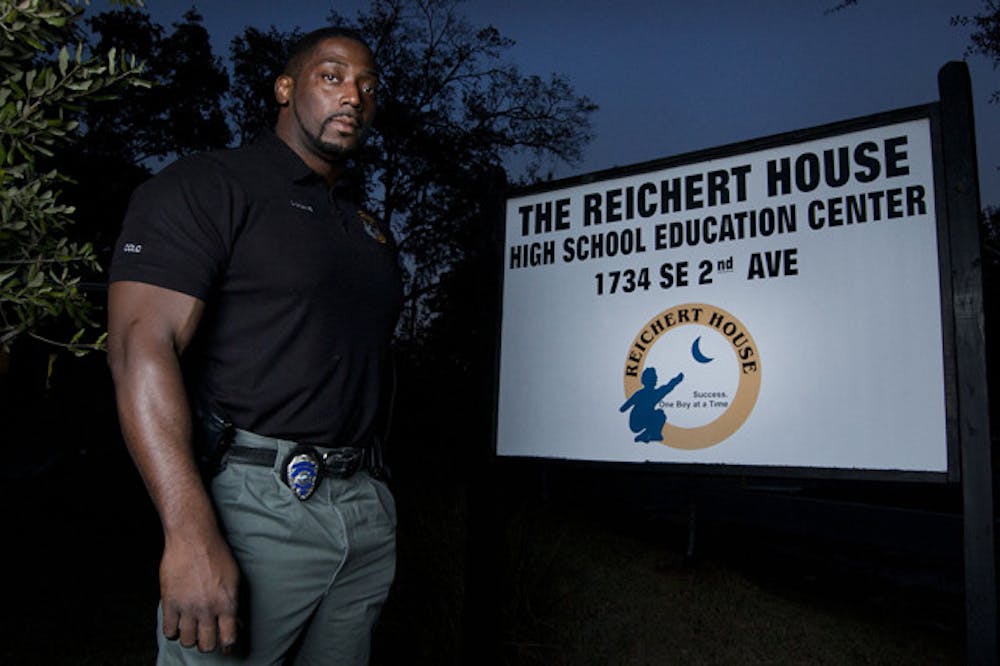

Williams, a GPD officer for 10 years who used to patrol downtown Gainesville, has worked at Reichert House for five years. He was originally an intervention specialist who counseled the kids and is now the program’s operations director.

He offers advice and help to all the boys at Reichert House, but for some he becomes a close mentor. He tells them when they’re messing up in school, and he helps them work through their problems.

If a boy needs to get out of the house to clear his mind, Williams might take him fishing on a weekend. Sometimes, the best thing he can do for a boy is to call him out on his mistakes and talk with his parents about how to help.

Najuan Williams, a 19-year-old alumnus of the program who still volunteers there, received support from Officer Williams that helped him control his anger. Shorter than many boys, Najuan would often lash out when someone tried to mess with him.

To help him release his anger without slugging another kid, the older Williams had him lift weights or practice boxing. This helped Najuan work out his emotions physically without pressing his fist to another person’s face.

Originally for boys involved with the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice, Reichert House now serves at-risk boys in general. A boy who qualifies for the program can have a variety of risk factors, from living in a single-parent home to getting poor grades.

Reichert House works with multiple organizations to develop and maintain its programs, including the city of Gainesville and UF. It is funded by donations and local and state money, according to the Reichert House website. Businesses can also contribute by becoming site sponsors that receive recognition for their support.

The after-school program runs Monday through Thursday. The middle school section focuses more heavily on discipline and preparing them for high school, while the high school portion encourages personal responsibility and free-thinking. Reichert House also has a summer program that runs all day on weekdays.

During the school year, the boys are picked up from their schools and brought to Reichert House. The program provides academic advising, counseling, paramilitary exercises and other services, Williams said.

Sherry Estes, assistant principal of student services at Eastside High School, provides academic help for the high school sector along with student volunteers from UF and Santa Fe College.

Estes has been involved with Reichert House for three years. She teaches math, advises students on academics and encourages them to study for the ACT and SAT.

In some ways, she and the other adults in the program are surrogate parents for the boys. They help them make decisions and don’t sugarcoat the truth.

As she shuffles papers on a desk in a Reichert House office, a boy in orange-and-black pants walks in the door to ask her about logging onto the ACT website.

As she answers his questions, another boy leans against the door frame.

“I got a 13,” he says of his ACT score.

Estes looks over at him sternly. “You’re going to take it again,” she says.

The boy mumbles and looks down, frowning.

“Hey. Not an option. OK?” Estes says.

No answer.

“Yes, Ms. Estes,” she answers for him.

The boy looks up. Not an option.

In addition to academics, Reichert House boys meet with intervention specialists who provide counseling and representatives from local organizations that teach them about health, finances and other subjects, Williams said. They also have time for recreation and get a meal before they are taken home in the evening.

The program meets the individual needs of each child and keeps them off the street during prime crime hours. In the last four years, 100 percent of the program’s senior classes have graduated from high school, Williams said. While some do end up in jail, most go on to college or junior college.

At Reichert House, Williams is the “silent hammer,” the fail-safe, the last line of defense. If a boy gets out of control, Williams steps in to handle the situation, whether that means calming the boy down, disciplining him or both.

On the lawn in front of the middle school phase of Reichert House, Williams talks with a young boy and his mom. The boy, Arkeem Bennett, has been getting poor grades.

Williams tells him he needs to do something proactive instead of mouthing off.

“Grades man, first and foremost,” Williams tells him, placing a hand on his shoulder. “Everything else will take care of itself.”

Arkeem, wearing a red T-shirt and carrying a backpack, looks at the ground.

“If you’re going to be a smart aleck, be one all the way and in there, too,” Williams says, tapping the textbook in the boy’s arms.

It’s time for Arkeem and his mother to head home, so Williams gives his shoulder a squeeze and smiles.

Arkeem’s mom turns to leave with her son but looks back at Williams. “Thanks, sugar.”

Williams is no stranger to what the boys of Reichert House are going through in their lives. He may be a police officer, but he’s also a Gainesville native with a rough past. He can relate to these boys because he’s been through it all himself.

Growing up in a single-parent home like many of the Reichert House boys, he did poorly in school and was often just seeking attention from anyone who would notice.

By 14, he had been shot and stabbed. He watched his best friend die from a gunshot wound right in front of him. When a boy like 16-year-old James Nixon, who was previously involved in gangs, joins the program, Williams understands the pressures he faces because he faced them, too.

“I don’t want them to go through what I went through,” Williams said. “If I reach one, I’ve done something. That’s one less I have to worry about being a tax-taker instead of a taxpayer.”

By working with the boys on a daily basis, Williams hopes to change their views of police officers. Many grow up seeing cops as the enemy, often because their parents view law enforcement that way. He wants them to see him, as well as other officers, as people who can help rather than hurt.

If a Reichert House boy runs into trouble, other officers know to call Williams to come work things out as long as the offense doesn’t require the boy’s arrest. He isn’t there to punish the children but to discipline them when necessary and help them handle the daily trials of home, school and tough neighborhoods.

For James, Reichert House became a place to learn leadership skills and to help others. When James first joined the program, he was still in the mindset of being a “knucklehead” and didn’t want to listen.

But as he became familiar with the children and adults involved in the program, he realized that he could embrace Reichert House and learn how to be successful in life, or he could just “come out dumb.” He decided to be successful.

James knows that when he needs Williams, he can call, and Williams will be there. In return, James will do any job Williams asks of him at Reichert House. They help each other.