In 1968, Hilary Sessions had a baby.

It was a child she fought for after family urged her to have an abortion, a child whose handprint she took in plaster when Tiffany was just 4 years old.

In 1989, Hilary Sessions lost her baby.

On an evening walk, the UF student disappeared, the plaster handprint a tangible reminder of a body that was never found.

Three years ago, Sessions drove from Tampa to Alachua County forensics to deliver the handprint. From the plaster, they lifted a single fingerprint.

It was one more piece of evidence for finding Tiffany and solving her mystery, one of 27 cold cases that still linger in Alachua County. Last month, the Florida Sheriff’s Association formed a committee to give greater attention to cold cases throughout Florida, a committee that Alachua County Sheriff Sadie Darnell helps lead.

"I know that my little girl will not be walking through the front door," Sessions said. "But there’s still hope for me to be able to give her a funeral."

• • •

On top of a shelf in Darnell’s office, there is a picture of two fingerprints.

The left print is clean, a stark impression made in a Alachua jail in 1977 after a burglary arrest. The right print is blotchy, a blurry imprint from cardboard in a Gainesville shed in 1995 after a sexual assault.

Both fingerprints belong to John Alexander Scieszka, a man with striking blue eyes who often wore a bandana over the lower part of his face when he committed crime.

After local authorities matched the description of the rapist to the burglar, they used the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Combined DNA Index System — referred to as CODIS — to link Scieszka to about 30 rapes between Gainesville and Georgia, Darnell said.

CODIS links DNA evidence and fingerprints from agencies across the country, and Scieszka’s case was the nation’s first match between two states. The fingerprints on the shelf help preserve both memory and motivation.

"It’s a reminder — constantly —that most cases can be solved," she said.

Darnell, a vice-chair on the Cold Case Advisory Committee, said the goal is to help large agencies that have too many cases and small agencies with too little resources.

"This is purposeful work, and it’s hard to remember that sometimes with all the negative feedback we that get," she said.

Detectives from around the state will present cases during a committee meeting next month, where members will review evidence and make suggestions.

Working in the present and planning for the future shouldn’t stop law enforcement from solving past cases, Darnell said.

"Loved ones and friends of someone who’s been murdered or remains missing — they never forget, nor should we," she said.

Any combination of crimes, such as rape and homicide, Darnell said, could be connected to the same person across the country.

In Florida, the focus recently became cases involving sexual assault after Florida Attorney General Pam Bondi began pushing a bill two weeks ago that would fund Florida Department of Law Enforcement testing of possibly thousands of rape kits sitting on shelves around the state.

A sexual assault evidence kit used by the Alachua County Sheriff’s Office includes vaginal swabs, a pubic hair comb, an underwear envelope and forms for the nurse to fill out.

The Alachua Sheriff’s Department started sending all rape kits to the Florida Department of Law Enforcement for testing in 2014, said Art Forgey, the Alachua County Sheriff’s Office spokesman.

"We have zero backlog of them; however, it is a national problem," he said.

Even if a victim doesn’t want to prosecute for rape, DNA could still link the crime to other offenses by the same person — including offenders in cold cases.

Using the William’s Rule, a case-law precedent established in the 1950’s, prosecutors could strengthen their case against an offender by presenting the evidence in a trial for separate crimes, Darnell said.

"We may hold the DNA that solves several cases," Forgey said.

• • •

There are more than 66,000 pieces of evidence in the Sheriff’s evidence room, according to Glynda Saavedra, the supervisor of evidence at the Alachua County Sheriff’s Office. All the way in the back — after walls of guns, baseball bats and desktop computers — is where Detective Kevin Allen draws from boxes marked with numbers and pictures for each victim.

"The likelihood of success is extremely slim, but you have to know we’re going to try," he said.

Two years ago, he left 24 years with the police department in Fort Lauderdale for a fresh start with cold cases, hired specifically to resurrect new leads in cases that go cold after all witnesses and evidence collections are investigated.

Boxes of evidence sit in an evidence room in the Alachua County Sheriff’s Office.

The wall of his office lists the names of victims and suspects, and binders full of case notes as wide as his hands line the shelves.

The office uses pictures to remember who they’re fighting for.

When the witnesses and reporters are gone, Allen and the victims’ families are sometimes all that remain.

"They’re always so grateful, and I say, ‘Are you kidding me?’" Allen said. "This is my privilege — I’m not the victim here."

He calls Tiffany’s mom "sis" in daily email conversations, and she calls him "bro."

"When Kevin came on, it was like the door opened and the light shone in," Sessions said.

Darnell refers to Allen as the cold case rock star.

"He is doing something every single day to solve a case," Darnell said.

Funding remains one of Allen’s biggest obstacles, despite the technological advances.

A Solving Cold Cases with DNA Analysis grant awarded the Sheriff’s Office more than $151,000 in 2010, but that money has since run out and the office pays directly for private lab testing, Allen said.

He said processing a single piece of evidence usually costs at least $1,000, and each case averages $20,000 to investigate. With the FDLE backed up with cases, Allen said his cold cases, which date back anywhere between 1966 and 2007, don’t get top priority.

But, with the DNA he already has, Allen is one step closer to solving the cold cases he has.

• • •

Twenty-six years after her daughter’s disappearance, Sessions, now 70, hasn’t given up.

She said DNA was too expensive and time consuming at first, but now a microscopic sample can be replicated and studied.

"I had to wait for technology to get caught up to what we needed to do."

In addition to the FDLE, other avenues provide services and hope, such as the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System.

Parents submit their DNA into the system in hopes of matching with their loved ones’ remains, and it compares new and current samples every night, Sessions said.

"There are 34,000 (unidentified remains), and one of those 34,000 may be my little girl," she said.

Sessions said she will stay hopeful that new resources and organizations will lead to the close of her daughter’s case and many others’.

For now, she embraces her evolution from a victim to a survivor, making speeches across the country and pushing for laws that keep America’s children safer.

And without fail, Allen will say how his "sis" knows how to take lemons and make lemonade.

"And I say, ‘Kevin, that’s what life is all about,’" Sessions said.

Contact Giuseppe Sabella at gsabella@alligator.org and follow him on Twitter @Gsabella

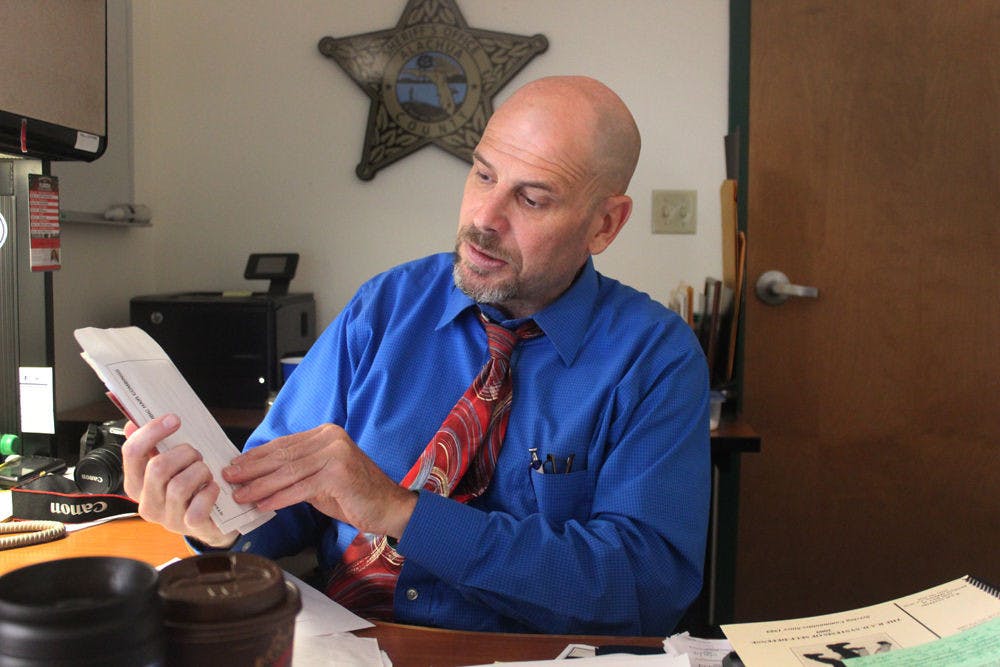

Art Forgey, the spokesman for the Alachua County Sheriff’s Office, goes through a sample sexual assault evidence kit in his office Sept. 16, 2015. ACSO is looking to use DNA from rape kits and other cases to solve cold cases. “Twenty years from now, who knows what we’ll be able to do,” he said.

Vaginal swabs are part of the sexual assault evidence kits used by the Alachua County Sheriff's Office.