In seventh grade, Camryn Ford felt lost.

His grades were slipping. College wasn’t on the table. Only outside the classroom did he feel he finally got the direction he lacked from school.

Hitting the books and the tennis courts every day after school for the past two years at Aces In Motion, a nonprofit built on tutoring and coaching East Gainesville middle and high schoolers, Ford feels set on a path toward Bethune-Cookman University, now his dream school.

“They gave us something to look forward to,” the Eastside High School ninth-grader said of how he felt when he joined AIM in 2015. “It’s just been crazy… to even go to college.”

Ford’s story — that of a young black student feeling left behind in Alachua County’s Public Schools system — is not unique.

For the past three years, Alachua County has had the largest achievement gap between white and black students on state exams across all 67 Florida counties, a Florida Department of Education information portal reveals.

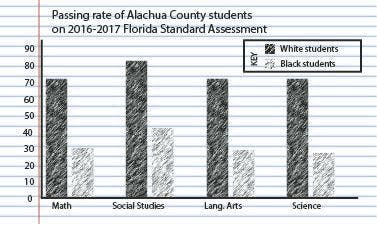

Alachua County’s black students significantly underperform compared to its white students across all four subjects of the Florida Standard Assessment, an end-of-the-year exam required for third through 10th-graders.

The exam is scaled one to five. Three or higher is considered passing.

Last year, the language arts FSA had a 45 percent achievement gap with only 29 percent of the county’s 5,982 black students between third and 10th grade and 74 percent of the county’s 7,678 white students passing.

The white-black achievement gap for the FSA mathematics exam was 42 percent, with white students passing at 72 percent and black students at 30.

On the social studies exam the gap was 42 percent.

For science it was 3 percent shy of 50.

For Hispanic students, who make up about 10 percent of the total student population, the achievement gap between white students was 20 percent on the language arts FSA, tied for sixth largest in the state.

Gainesville resident Anne Koterba said her heart breaks as she sees the white-black achievement gap fail to improve.

Far too often the gaping race problem in public education is forgotten, said Koterba, who collects education data for local groups including Gainesville For All, which will make demands before the school board early next year.

“People like me, white people, look at problems in the school being like a parent problem, ‘Oh those parents, oh those kids don’t want to learn,’” Koterba said. “You’ll hear that all the time from white people, but black people don’t see it that way; they see the system that set all this up.”

The No.1 reason for the gap is poverty, ACPS spokesperson Jackie Johnson said.

According to FDE enrollment data, 59.7 percent of the 16,332 students considered economically disadvantaged this year are black.

Overcrowding is an issue in West Gainesville, and more than 300 portables are used countywide, Jackson said. The school board will start talks about building a new elementary school in West Gainesville in February.

She also stated a reason for the achievement gap is that Alachua County’s white students perform extremely high — not that black students are performing as poorly as in other Florida counties, she said.

The district is still very much committed to increasing black achievement, she said.

“We’ve set very specific targets for each one of our schools that are focused on the performance for African-American students and economically disadvantaged students,” Johnson said.

In July, the school board appointed a new equity director, Valerie Freeman. As of press time, Freeman could not be reached for comment.

Chanae Baker, a Gainesville mother of three and education activist, said higher white performance shouldn’t excuse the gap.

“Our black students are in the last quartile,” Baker said. “These are students that are in the exact same schools; there’s no reason they should be so different. We’ve got a real problem here.”

Every time Baker hears of limited resources for eastside schools, she said thinks back to Sept. 29, when she organized a march to fight against the district’s decision to remove Eastside High School’s “courtesy bus,” which transports kids who live within a two-mile radius from the school.

All the while she was organizing the march, Baker said the district never considered taking her 17-year-old son Deonis’ bus away, despite the fact they live less than one mile away from where he goes to school, Buchholz High School.

Baker said the first step to addressing equity and black achievement is to make it a priority and outline real, concrete steps — like rezoning and diversifying eastside schools.

“We have the resources; it’s about where we’re putting them,” she said. “We have a habit of talking about how we’re going to fix it, but we need to actually step up and do something.”

***

After 14 years teaching 11th and 12th grade English at Eastside, Amanda Lacy-Shitama said she’s seen the pattern.

More than 90 percent of her students are black.

Outside her classroom, Lacy-Shitama said every day she witnesses some aspect of the divide between the school’s International Baccalaureate program and “major” program.

The signs of de facto segregation are everywhere, she said. “Major” kids, who are majority black, sit inside the cafeteria during lunch time, while IB kids (majority white and Asian) take to the outdoor tables.

During a recent fire drill, her students even pointed out to her the areas of the student parking lot that are IB and major.

“They said, ‘Oh look Ms. Lacy, this where the black kids park, and that’s where the white kids park,’” she said.

Eastside IB alumnus Carsten Thue-Bludworth’s only exposure to major program kids was outside of the classroom. During class hours, Thue-Bludworth remembers the two groups rarely mingled.

But after school when he was involved with track, cross country and jazz band, he had his only chance to meet up with kids in the major program and make lasting friendships.

“I was always fortunate, I felt, and like happy to have that exposure,” he said. “I know a lot of kids didn’t have it.”

The disparities manifest themselves in racially divided test scores, even internally within schools with successful magnet programs.

At Eastside last year, only 17.8 percent of black 10th graders passed their language arts FSA exam, contrasted with 89.8 percent of white students who passed, according to FDE testing data.

“With a lot of my kids, it’s not a question of their intelligence or whether they’re smart; they are,” Lacy-Shitama said of her Eastside High students. “There’s not a lot of support for them.”

As she hears stories of overcrowding in westside schools, Lacy-Shatima said all she can do is look at some of the empty seats in her own classroom.

“We’ve got plenty of room here,” she said.

----

For Addison Staples, change comes by inspiring one teenager at a time.

Staples started his Aces In Motion youth program in 2011 as a way to mentor underprivileged kids through tennis lessons after school. Then the 34-year-old started asking about their goals — and their grades.

As and Bs, sure, Staples said. But some had Ds, even Fs.

“You quickly realize that reality was going to be hard for them if they continued making those grades,” he said. “Their dreams and goals — it would be a tough road to achieve those.”

That’s when Staples shifted his program to focus on academics.

Now, every day Staples’ 35 middle schoolers and about 14 high schoolers — including 15-year-old Camryn Ford — play hard and study hard for three hours at both the Florida Gym and the TB McPherson Recreation Complex, located at 1717 SE 15th St.

Starting at 3:30 p.m. it’s school work. Staples usually has about 20 volunteers, some UF students, to give tutoring to the kids. Then it can be anything from tennis to life skills to even music and dance lessons.

All of his students come from either Lincoln Middle School or Howard W. Bishop Middle School, even the high-schoolers who started the AIM program as middle-schoolers. East Gainesville is the area that by far has the most need, he said.

“These schools are split into two; everybody knows it,” he said. “You’ve got your magnet and your gifted program and then your main program, which will be 90 percent African-American youth.”

Overcapacity at westside schools and under capacity on the east side is just the symptom of a larger issue, Staples said. He sees the real issue as the systematic, generations-long neglect of Gainesville’s black youth.

Staying involved is the best way he feels he can help, Staples said.

“A lot of the kids have an uphill battle,” he said. “If we can do anything about it, that’s what we’re going to try.”