Mackintosh Joachim said he’s sick and tired of being sick and tired.

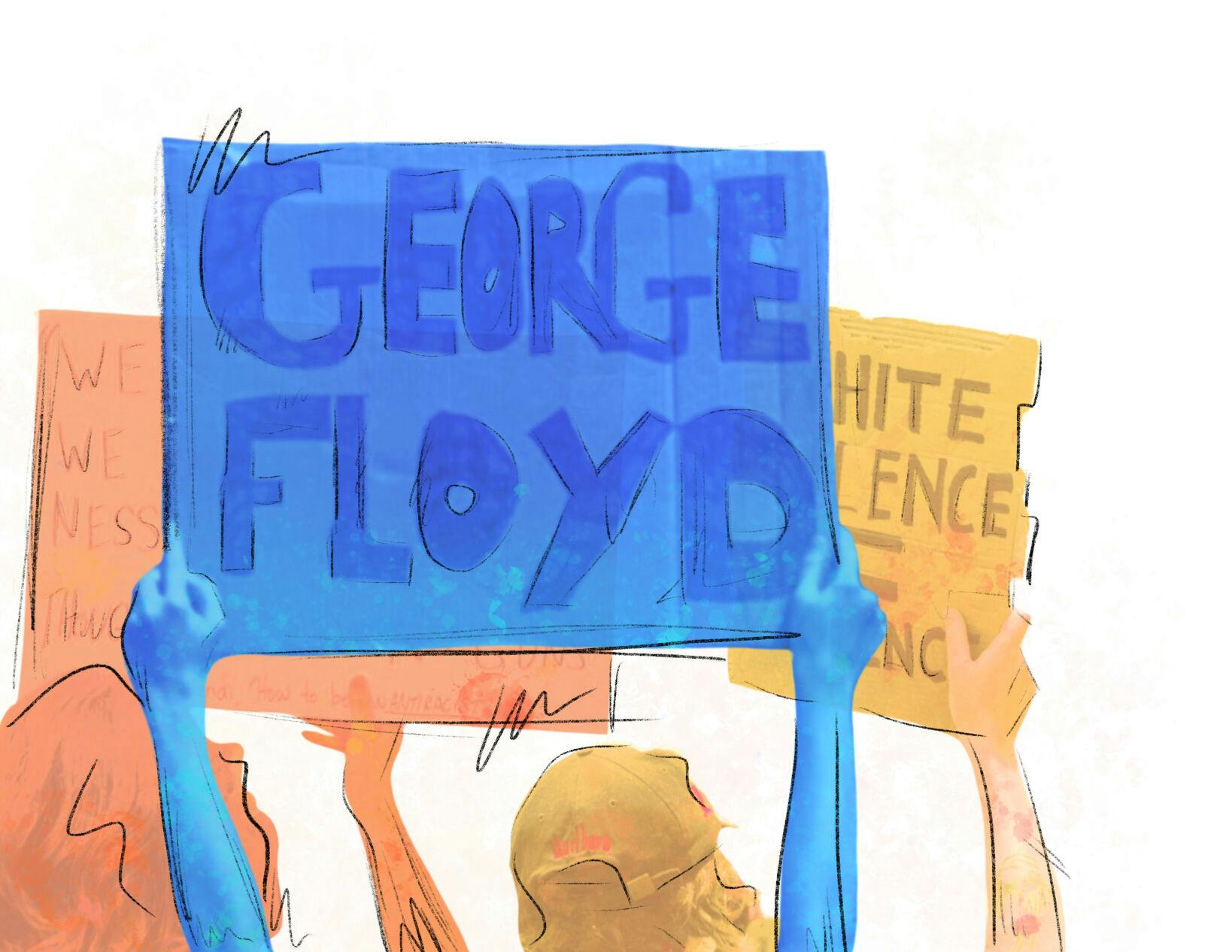

The 21-year-old UF political science and women’s studies senior said it’s difficult to describe his experience growing up as a black person in America, where the color of his skin equates to a threat. After the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer on May 25, the difficulty only mounted.

Joachim, the president of UF’s NAACP chapter, has an unshakable fight-or-flight response when he sees the red and blue lights of a police car nearby.

A routine interaction with police shouldn’t be a prison sentence, Joachim said—and for many people, it isn’t. But for black Americans, it often is.

“We are arrested,” he said. ”Or we end up dead.”

Patricia Hilliard-Nunn, a senior lecturer in UF’s African American Studies program, said today’s justification of police brutality is not so different from the justifications used in the 1900s. Hilliard-Nunn studies the history of lynching of black Americans in Alachua County.

“There's nothing new going on,” Hilliard-Nunn said. “It's really simply an updated version of what black people have experienced in the United States of America since its inception.”

Law enforcement officers often took part in lynchings in the past, she said, but were never prosecuted. Their colleagues were usually part of the grand jury.

Hilliard-Nunn said that television and social media have given many people their first glimpse into the mistreatment of African American people, and as awareness grows, so does public outrage. Still, it’s not enough.

Not enough people are properly educated on white supremacy and how it has been used to systemically oppress black people, she said.

“Everybody will get upset, then everybody goes back to sleep––then something else happens because they never did anything,” Hilliard-Nunn said. “To do something means that you really have to dismantle practices that have been in place for a long time.“

To dismantle those practices, Hilliard-Nunn said, education is key. Greater awareness of lynching, killing and false imprisonment of black people could help bring about change.

“People need to unlearn racist beliefs, some of which make them see black people as criminals,” Hilliard-Nunn said. “When a person or society does not see your humanity, they have no problem lying about you, marginalizing, enslaving you, discriminating against you, lynching you, etc.”

UF’s African American Studies program began as a certification but is now moving toward establishing itself as a department. Department status will allow the program to hire more employees and to better educate students at UF, Hilliard-Nunn said.

UF President Kent Fuchs released a video on Twitter Friday condemning Floyd’s murder. He encouraged viewers to reflect on their biases and to educate themselves on racial injustice.

Later, UF Vice President for Student Affairs D’Andra Mull sent an email to students that said she recognized feelings of frustration and sorrow amid COVID-19 and racial violence. Mull said Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and Nina Pop were victims of racism and hate.

She misspelled Taylor and Arbery’s name in the email.

“UF please stop,” Joachim wrote in a Facebook post, where he included a photo of Arbery’s misspelled name. A correction was issued, but Joachim said he felt the damage was already done.

Sara Tanner, the UF Student Affairs director of marketing and strategic communications, said the misspelling of the two victims' names was an egregious mistake.

“That is very disrespectful,” Joachim said in a phone call. “It shows that UF never cared. What got me is that the student affairs vice president is a black woman, and she allowed that to go out.”

Jalyn Hollis, a 19-year-old UF finance sophomore, said that while she appreciates the university’s decision to speak out and sees it as a step in the right direction, statements on social media don’t stop race-related incidents from occurring on campus.

Actions speak louder than words, Hollis said. The university’s own history with race and racism make public statements like Fuchs’ seem disingenuous, she added.

UF faced backlash in 2018 after it received an F ranking in a University of Southern California Race and Equity Center study determining racial representation. The study showed that African American students make up only 6.1 percent of UF’s student body.

In October 2019, UF Student Government brought Donald Trump Jr. to speak on campus. The event was met with protesting students chanting “Black Lives Matter” throughout the event.

The following month, a black student was called the N-word by a white student in a SNAP van. While UF’s Institute of Black Culture opened a day after, many saw the building's opening as a facade that hides the reality that African American students face at UF.

Hollis said she was shocked to hear of the university’s low race equity ranking. But she understands that African American students often feel that their voices don't matter, she said.

“Skin color does make it harder,” Hollis said. “Sometimes, being the only black person in the room, I definitely feel like things can be difficult when you feel like you're outnumbered.”

Hollis said the university could do a lot more to improve how race-related incidents are handled. Nevertheless, she said she supports Fuchs’ message to students about questioning their judgements and educating themselves.

Hilliard-Nunn said citizens must speak up and encourage the passage of anti-police brutality policy to ensure that the abuse stops.

“Unless our nation addresses systemic racism and white supremacy, nothing will change,” she said.

Contact Nicole at nrodriguez@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @_nrodriguez99.