As voters head to the polls on Election Day, beneath the names of high-profile candidates like Rick Scott and Marco Rubio they will see a list of six proposed amendments to the Florida Constitution.

The language can be dense and the arguments exhausting, but this season’s string of amendments gives voters a voice on class size, legislative redistricting, land use and other issues. With controversy surrounding most of the proposals on the ballot, an educated vote means knowing what each mean.

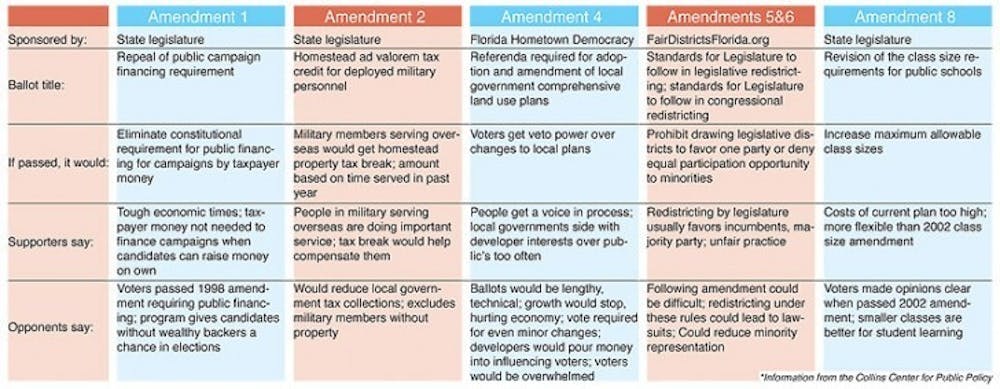

The Alligator compiled a list of pros and cons and analysis from UF professors to help explain this year’s amendments.

Amendment 1: Repeal of public campaign finance

This proposal would eliminate a 1998 amendment that made public campaign financing a requirement. The amendment would provide legislators the chance to pass laws removing the public financing program if it passes, according to a report from the Collins Center for Public Policy Inc.

The Republican-dominated state legislature supported putting this amendment on the ballot.

Supporters believe the proposal makes sense given the tough economic situation because it would remove the mandate that taxpayer dollars be used to support candidates who can, and often do, raise money on their own, according to a Collins Center report.

Those opposed argue that voters already voiced their opinions in 1998 with the amendment that added public financing to the constitution and that public financing gives candidates without wealthy backers a better chance in races.

Richard Scher, a UF political science professor, said the possibility for non-wealthy candidates to emerge in election races would be almost impossible if the amendment passes.

“It really doesn’t matter for the Rick Scotts of the world,” he said, referring to the Republican candidate for governor who has invested more than $70 million in his campaign.

Kristin Klein, president of UF College Democrats, worries that candidates would become more tied to special interests if the amendment passes because they would be more dependent on them for financing without a public option.

Amendment 2: Tax break for deployed soldiers

This amendment would require the state legislature to give an added homestead property tax break for members of the U.S. military and its reserves, the U.S Coast Guard and its reserves, and the Florida National Guard on active duty outside of the U.S. in the past year.

This amendment is probably the least controversial of the six on the ballot, with no organized opposition to it.

It would help compensate military members for their services overseas, although it would also lead to a decline in local government tax collections and would exclude members of the military who don’t own property. Tax breaks would be determined by how long someone served overseas. For example, if someone was deployed outside the U.S. for six months, he would get a 50-percent exemption.

Scher expects the measure to pass, but said that even noncontroversial amendments can face challenges.

With the constitutional amendment passed in the last election requiring a consensus of at least 60 percent to pass these measures, he said it is hard to decide whether Amendment 2 or any of the others have the horsepower to pass.

Amendment 4: Hometown democracy

One of the most controversial amendments, it would require voters to approve any proposals to adopt or amend local comprehensive land use plans (growth-management plans).

Florida Hometown Democracy Inc., an organization that began getting petition signatures in 2003 for the amendment, and other supporters believe the proposal would give voters a chance to prevent local governments from placing developers’ interests above those of their constituents.

Many developers, politicians and other opponents argue that the amendment would create unwieldy ballots that are too long and too technical, overwhelming voters.

Katrina Schwartz, a UF political science professor specializing in environmental politics, said the amendment could be a wake-up call to legislators about voter demands that they crack down on development and not defer to developers’ desires.

It won’t prevent developers from using money to influence the process, however, but will just shift their focus, she said. Instead of directing persuasive efforts toward local governments devising plans, they would bombard voters with information supporting their particular plans. Voters may not have the time or desire to learn enough about the intricacies of land planning to make educated decisions about these plans, she said.

Ryan Garcia of the UF College Republicans said he is concerned that Amendment 4 would lead to an increase in property taxes and that it would become a “blank check” because budgets don’t have to be disclosed to taxpayers.

He also doesn’t think it would give voters a real voice because of the probable low turnout rates for such decisions.

Gainesville City Commissioner Jeanna Mastrodicasa is opposed to the amendment because, while she believes it is well-intended, she said it would only give developers more power and make reading through ballots less appealing to voters.

If people are unhappy with land planning decisions, they should elect new officials who will make better ones, she said.

The City Commission decided to oppose the amendment officially with a 6-1 vote in July. Commissioner Thomas Hawkins said he is concerned that the amendment would prevent meaningful conversations about land planning between local officials when they know it will ultimately come down to an “up or down” vote by the public.

Amendments 5 and 6: Changes to redistricting

These amendments would prevent politicians from drawing legislative districts to favor one party over another.

Districts are redrawn every 10 years and are marked by political clashes, as the majority party often tries to design districts to protect its majority and incumbents (gerrymandering.)

“There’s always blood on the floor when they do reapportionment,” Scher said of the process.

If passed, the measure would give a voice to the people who demand that redistricting be a fair process rather than an “incumbency protection plan,” he said. However, even if the amendments pass, redistricting would remain in the legislators’ hands, and Scher said he doubts the amendments would eliminate gerrymandering problems.

The amendments would provide standards for judges to refer to and would allow them to make decisions about redistricting plans. There are no standards for redistricting in Florida now, so judges have little revision power.

Opponents argue that the requirements may be difficult to follow in practice and that it may hurt minority representation because legislators wouldn’t be able to draw districts balancing the political “playing field” for minorities.

Hawkins supports these amendments, which would help prevent legislators from drawing districts along lines that divide neighborhoods among different representatives. Communities can be divided into districts under the legislature’s usual methods, which can make it difficult for representatives to adequately represent all their constituents, he said.

Mastrodicasa also supports the measures and said she knows people from both parties who support them, as well.

They would prevent legislators from giving too much power to the incumbent party, regardless of which one is in power at any given time, she said.

Another measure about redistricting, Amendment 7, would have essentially nullified Amendments 5 and 6 if passed. But the proposal, which was added to the ballot by the Republican-controlled legislature, was removed from the ballot by a circuit court judge’s order.

Amendment 8: Relaxing class size requirements

This would increase the maximum number of students allowed in a class, changing from a maximum number per class to a school-wide average. For example, a high school could increase one class’s capacity to 30 students as long as another class had fewer than the average class size of 25 students.

Supporters argue that the cost of limiting class sizes is too high and that this would save money and provide flexibility.

A July report by Florida TaxWatch’s Center for Educational Performance and Accountability estimated that the state could save about $10 billion during the next decade if it passes.

Opponents argue that these savings could mean further cuts in education funding because schools would not receive any of the money allocated for the original plan. They say voters were clear in 2002 when they passed the first class size amendment.

The Florida Education Association is one of the organizations opposing the measure. It filed a lawsuit challenging the bill, but the Florida Supreme Court upheld a circuit court judge’s decision to keep it on the ballot.

Scher said he thinks the amendment is another attack on public schools. Teachers will bear the burden if this amendment is passed, but the losers will be the students, he said.

Klein expects Democrats to vote against the measure and Republicans to support it.

“Even though a lot of people say it only increases the class by three or four [students], when are they going to stop? There’s a cap for a reason and it needs to stay,” Klein said.

For pre-kindergarten through third grade, the amendment would set an average class size of 18 students and a maximum of 21. For fourth through eighth grade, the average would be 22 students with a maximum of 27. For high school, the average would be 25 students with a maximum of 30.