Josiah T. Walls fought on both sides of the Civil War, served as Gainesville’s mayor and became Florida’s first black representative.

But when he died, few heard of it.

Without a word and without a marker.

Walls might be one of the lesser-known black Florida leaders in the state’s history. He was born into slavery in 1842 in Winchester, Virginia. He later became the only person in Alachua County’s history to serve as the Gainesville mayor, a county commissioner, a school board member, a state senator and a U.S. congressman. With that, he laid the groundwork for the Civil Rights era to come a century after him, but many today are surprised to learn he ever existed.

He became so obscure in the state he used to represent that when he died, his obituary was not published in a single Florida paper.

Today, no one knows exactly where he was buried. Most historians say he is in a blacks-only corner of a Tallahassee cemetery. Some have theories he made his way back to Alachua County.

Instead of a tombstone, his name is now prominently displayed in downtown Gainesville.

In 2016, more than a century after his death in 1905, the County Commission decided to give the building located at 515 N. Main St. a namesake.

It proved to be a significant moment for some and was a nod to a city attempting to redirect the attention of its history, but with a Confederate statue named “Old Joe” still sitting half a mile away.

The Josiah T. Walls Building now houses the Alachua County Supervisor of Elections Office and the Alachua County Property Appraiser.

During the building dedication on Oct. 16, 2016, just-elected incoming Supervisor of Elections Kim Barton was invited to unveil a plaque for Walls in front of the building.

Barton said she felt a connection.

He was the first African American to hold many significant elected positions in the county, and she was now the first African American to be its supervisor.

“It was just a proud moment for me. I hadn’t even taken office,” she said. “I just want people to know the history of this man.”

Before Walls made his mark in Florida, he was forced to fight with the Confederate States Army during the Civil War. He ended up on the Union’s side after escaping. He was one of few soldiers to fight on both sides of the war.

His regiment in the Union Army moved him to northern Florida in early 1864. He then met and married Helen Fergueson and had one daughter named Nellie.

After he was discharged a year later, he decided to stay in Florida. He moved to Alachua County and worked at a saw mill and then as a teacher.

“He came to Florida after the Civil War for many of the same reasons that white people came here, which is because he wanted to make a difference,” UF history master lecturer Steven Noll said.

Gainesville was a vibrant, mostly black community with about 2,000 people when Walls arrived. He saw economic opportunities, but he also saw the opportunity to improve the lives of his fellow African Americans.

He became a prominent member of the city. He had his hands in black newspapers, black education and black businesses. He also practiced law for a time.

He bought a large orange grove just outside of Gainesville and shipped his oranges into the city by boat through what is now Paynes Prairie Preserve State Park. A man born a slave now had his own plantation.

Walls was one of the few educated black men at the time in Florida, and he was drawn to politics.

He benefited from the era of Reconstruction. White Southerners were disenfranchised after the war. The black vote had power for once in U.S. history.

“He’s not running for office just for him,” Noll said. “He’s running for office for his race.”

He started in state politics. First, a term in the House and then two in the Senate. Then, he decided to run for Congress, but not without contention.

Walls beat out a conservative white Lake City man in 1870 for a congressional seat, but his win was narrow. Whites accused him of fraud. Walls served two months of his term before he was booted out.

This didn’t discourage him from running again. He campaigned and won re-election to a full term in 1872.

He ran a third time in 1874, beating J.J. Finley, a Confederate general from Jacksonville (who is also the namesake of an elementary school in Gainesville), by fewer than 400 votes. Finley contested the result. Walls got the boot again after serving for a year.

“It’s interesting that Gainesville remembers Finley but not Walls,” Noll said.

Florida’s second African American representative did not come until a century after Walls in the 1990s.

While serving in Congress, not only did Walls advocate for the rights of African Americans, but he also pushed for support of projects to benefit all Floridians, such as the construction to build a canal across the state. This helped him gain respect from white voters, who may have just seen him as out for black interests.

After his time in national politics, he stayed in Gainesville, tending to his plantation and serving on the Alachua County Commission and as Gainesville’s mayor.

A freeze in 1894 wiped out his orange grove, and he moved to Tallahassee. He became a faculty member of what is now Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University, teaching agriculture to black college students. He told them how to benefit from the industry that was forced on their parents and grandparents.

He died in 1905. It cannot be found in any major paper in Florida.

Noll said this shows the stronghold Jim Crow laws had on the state at the time and the disappearance of the short-lived Reconstruction era.

The “Old Joe” statue was erected in Gainesville the year before Walls died, showing the values of the decade.

In addition to the building, Walls’ name is carried on with the Josiah T. Walls Bar Association, which was established in 1977. It is a voluntary minority bar organization with about 20 members, said AuBroncee Martin, an attorney with the Office of Public Defender with the 8th Judicial Circuit Court.

“He was a man who believed in service. He was a man of many talents and used his talents to the fullest extent that he could. He was a servant. A person who should use his talents for the betterment of the community,” Martin said of Walls. “It’s part of this community’s legacy, and it’s part of a foundation that greatness can be built upon.”

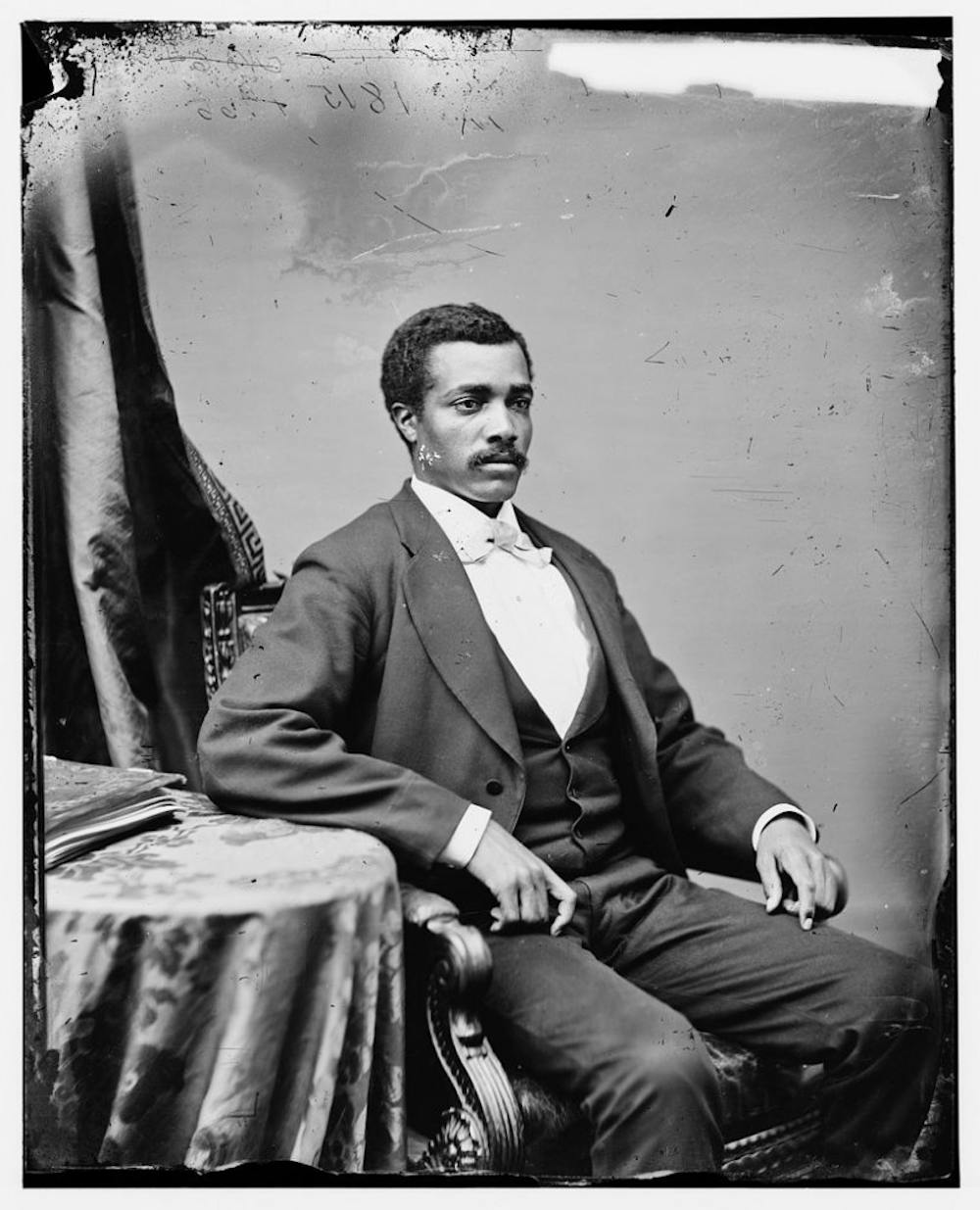

Josiah T. Walls, 1842-1905, was Florida’s first African American representative. He is the only person in Alachua County’s history to serve as the Gainesville mayor, a county commissioner, a school board member, a state senator and a U.S. congressman.