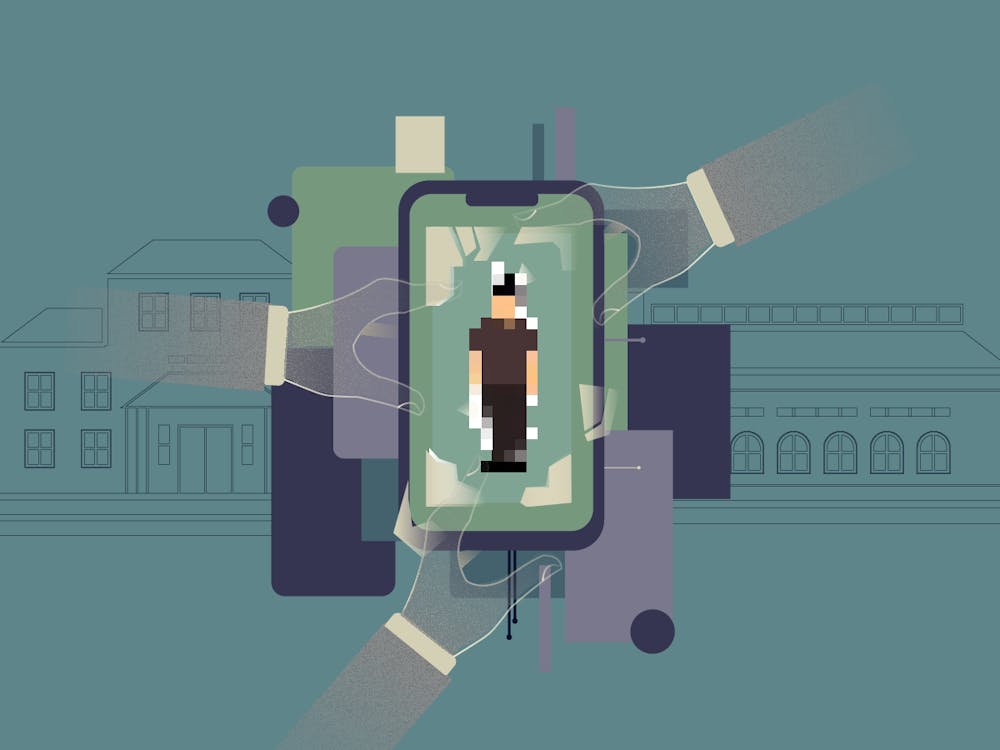

A single click can turn a private moment into permanent public exposure.

Madison Kowalski imagined a future as an actor. After an intimate video was shared without her consent, she says that future now feels uncertain.

Kowalski, a 19-year-old UF media production, management and technology sophomore, said her life has changed drastically in the three months since a nude video of her was posted online. Even simple tasks have become difficult, she said, describing mornings when anxiety left her unable to move or speak.

“I just saw my entire life fall apart in front of my eyes,” she said in an interview with The Alligator.

Her experience is not isolated. Nonconsensual intimate image abuse has become an increasingly common form of digital harm. Research suggests that anywhere between 6% and 32% of young adults have experienced NCII, depending on how the definition is applied.

NCII includes a wide range of behaviors, from the sharing of private sexual images without consent to threatening or coercing someone using intimate photos or videos.

In Florida, the nonconsensual sharing of intimate images is a crime under the state’s sexual cyberharassment law. The law, first enacted in 2015, has been amended over the years to refine its definitions and penalties. In 2025, the statute was amended to clarify that intimate images do not need to include personally identifying information to be considered criminal.

National research from the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative shows women report higher rates of NCII than men. At UF, where women make up more than half of the student body, complaints must be submitted formally to the Title IX office to be investigated.

Impact on mental health

After Kowalski discovered nude videos of herself being posted on social media, she said, her roommates began receiving harassing phone calls. The situation escalated to the point that her parents learned what had happened. Kowalski described them as “very supportive."

The online harassment soon spilled into her offline life. She said she has lost friends and is often harassed by strangers in public. To “blend in,” Kowalski dyed her hair blonde and now takes online classes.

“My entire life changed in one day, because somebody posted something that wasn’t theirs to share,” she said. “That needs to end.”

Julie Stout, a Gainesville-based mental health counselor, said she has worked with UF students affected by NCII for three years. She said many of her clients are from Greek life, but she’s also seen international and LGBTQ+ students.

“When it’s online, or you’re getting any kind of harassment that comes through text or email, it follows the victims into their safe spaces,” Stout said. “It’s in their home — in their sanctuary — where they’re supposed to feel safe.”

Victims of NCII may experience anxiety, depression, panic attacks, sleep disturbances and a loss of self-worth, Stout said.

She added many students don’t know how to report NCII and sexual assaults, and short-term counseling services offered at UF sometimes aren't enough to help students address deep trauma. UF’s Counseling and Wellness Center defines short-term counseling as a maximum of 12 sessions.

Stout noted that victim advocates at UF have helped students in the past.

“It’s not just a social media issue,” she said. “It’s a public health and safety issue, and it’s definitely something that deserves to be taken very seriously.”

University reporting and institutional response

UF’s gender equity policy, which was last updated three years ago, defines NCII as a type of sexual exploitation. While sexual exploitation does not meet the qualifications for a Title IX violation, it falls under the university’s list of prohibited conduct, according to documents obtained by The Alligator.

Therefore, NCII incidents reported to UF’s Title IX office may be referred to the Office of Student Conduct and Conflict Resolution, which handles conduct violations.

Conduct violations can hold students accountable for off-campus activities. Title IX, on the other hand, can only investigate incidents taking place within university programs or on university-controlled property that involve UF-affiliated individuals.

The Office of Gender Equity and Accessibility was historically tasked with investigating cases of sexual exploitation, until a 2024 restructuring split the office into two departments handling Title IX and the Americans with Disabilities Act. The Title IX Office and Office of Student Conduct and Conflict Resolution now handle many of these cases.

Last July, UF adopted a new Title IX policy requiring all employees to report suspected sexual harassment or assault, dating or domestic violence and stalking. Students who file a Title IX request are not required to move forward with an investigation, though they may still be given confidential resources, like crisis support or a referral to another agency.

UF spokesperson Cynthia Roldán, in an email statement to The Alligator, said any student or employee who has witnessed or been the victim of harassment should file a Title IX report online.

“UF has zero tolerance for any form of harassment and promptly addresses allegations of prohibited conduct,” Roldán wrote.

Sara Smith-Paez, a GatorWell health promotions specialist and prevention educator, previously worked with students affected by NCII at Stetson University. She now leads workshops at UF on sexual violence and relationships.

Smith-Paez said intimate images are not always shared for revenge. Stalkers, for example, may use NCII to force contact with their victims.

While images can be removed through websites like StopNCII.org, Smith-Paez said, students who share intimate images should avoid including their face or any identifiable information. She suggested wearing different jewelry when sharing images with multiple people, so it’s easier to tell who shared them if they’re leaked.

“Prevention is on the end of the sender in some ways,” she said, “but it’s more so on the end of the people who would cause harm.”

How technology amplifies the damage

As technology becomes more advanced, experts warn the potential harm of NCII is expanding. Earlier websites like Is Anyone Up? allowed for the widespread distribution of NCII. The website shut down in 2012, and its founder, Hunter Moore, later served a federal prison sentence.

Now, experts warn that artificial intelligence could take the harm further by creating realistic deepfake images from just a single photo. A deepfake is a type of AI used to create realistic pictures, videos or audio that show a real person doing or saying things they never actually did.

Patrick Traynor, interim chair of UF’s computer, information science and engineering department, recently advised a paper analyzing the most popular websites that use AI to create nude images from photos of real people.

Traynor said that people have created fake images for “as long as tape has existed.” What concerns him is the accessibility of AI platforms.

“Five to 10 years ago, maybe if you were really technically savvy, you could do this kind of thing,” he said. “But for now, for as little as six cents an image, anybody can.”

Traynor’s team, which included researchers from the University of Washington and Georgetown University, spoke with victims of NCII and representatives at both the state and congressional levels. He said lawmakers were open to learning about the issues AI can cause.

“Technologies go hand-in-hand with economics, with laws, with societal norms,” he said. “All of those things together make real-world solutions.”

Omny Miranda Martone, founder of the Sexual Violence Prevention Association, said AI-generated NCII is beginning to be addressed at a national level. Martone is the author of the Defiance Act.

The national bill is intended to complement the Take It Down Act, which was signed into law last year and criminalizes the creation of nonconsensual AI pornography. It also requires image-hosting platforms to remove NCII within 48 hours of a report — a provision set to take effect in May.

Martone said the Defiance Act would address weaknesses in the Take It Down Act by allowing victims to sue in civil courts.

“Civil liability and a civil right of action for victims to see justice tends to be a lot more effective in both getting victims the resources and the help and support that they need,” Martone said.

Martone also said addressing NCII requires coordination between federal and state laws. A December executive order discouraging states from enforcing their own AI regulations has complicated that effort.

“It’s already making it difficult for states to pass and enforce existing laws,” Martone said. “Some states have decided to move forward. Other states seem confused and don’t know what to do.”

Contact Julianna Bendeck at jbendeck@alligator.org.

Julianna is a first-year journalism student and The Alligator's Spring 2026 race and equity reporter. She was previously an editor for Eagle Media, Florida Gulf Coast University's student newspaper. In her free time, she enjoys playing video games and reading. She is hoping to attend law school in the future.