For decades, experts warned University Avenue wasn’t safe.

They warned the road was too fast and pedestrians were too exposed. But the city and state ignored their caution. Traffic thickened, the road expanded, development boomed and foot traffic increased.

Then the crashes started. Lives were lost, and the warnings came too late.

University Avenue, one of the main east-west arteries running through the city, evolved from a dirt road into a four-lane highway bordering UF’s campus. It’s now the heart of the UF community — the north side of the road boasts nightlife at Midtown, a complex of bars, clubs, late-night restaurants and growing student apartments. UF campus and Midtown pack the road’s sidewalks with pedestrians day and night.

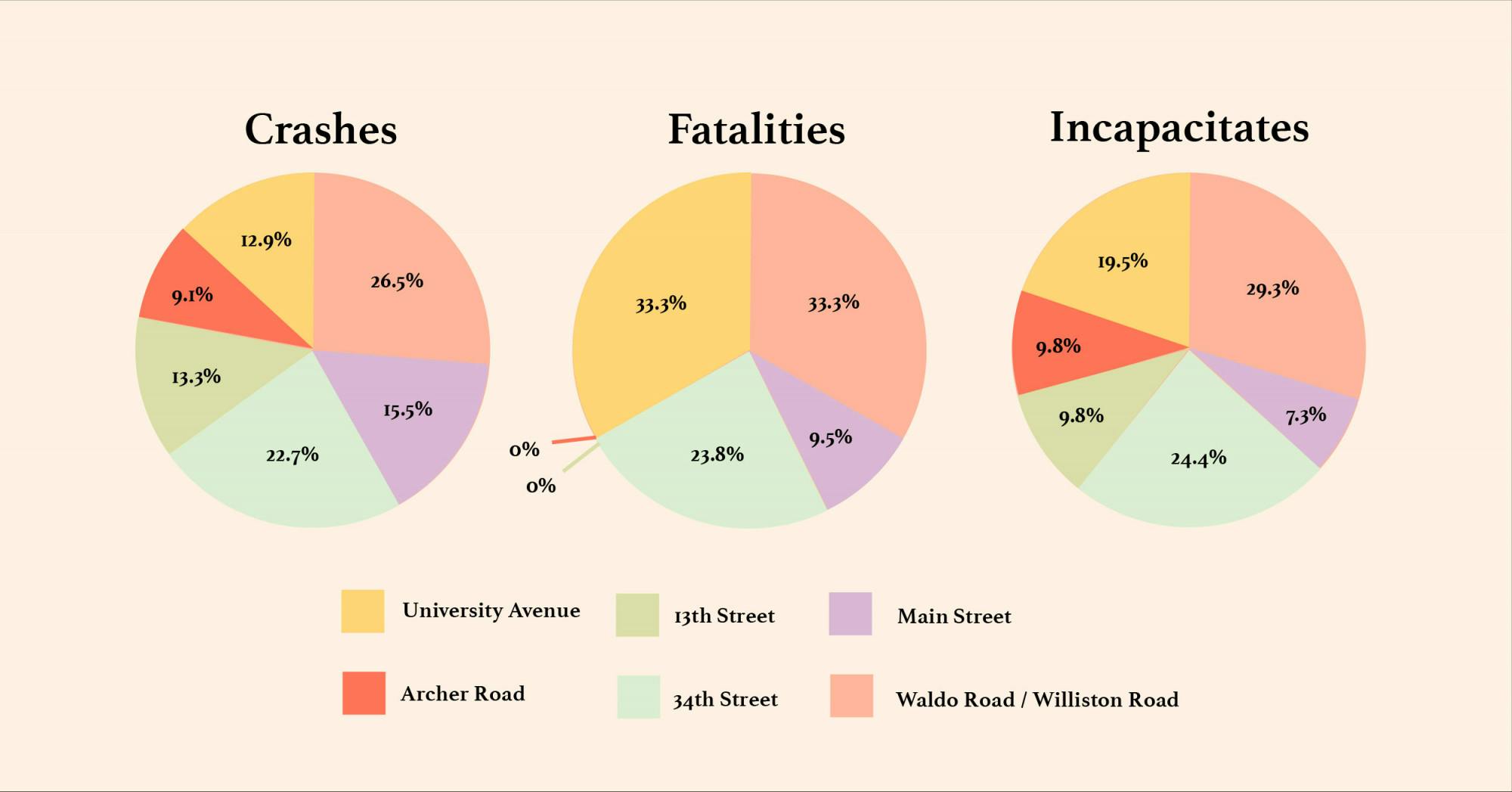

Yet, it is one of the most dangerous roads for pedestrians in Gainesville. Since 2016, it’s seen the highest number of the city’s pedestrian crashes — 70, according to data from the Gainesville Police Department. Seven have been fatal.

It ties with Waldo Road as the deadliest road in Gainesville. University Avenue’s crashes are also more likely to create incapacitating injuries, injuries that are non-fatal but prevent the injured person from continuing normal activity. Crashes on the road resulted in 12 incapacitating injuries in the past five years — the most of any road in Gainesville.

University Avenue’s expansion in the 70s and 80s began a decades long battle over driver comfort versus pedestrian safety. National city planners, local pedestrian activists and the Gainesville government have waged war over the road’s design ever since, but most attempts to dramatically change University Avenue’s design failed –– until this year.

The state and city stayed stubborn about the road for decades before. Driver-oriented politicians and businesses in fear of losing customers fought city planners to keep the roads wide and fast. And even when Gainesville made efforts to protect pedestrians, Florida state agencies shut down redesigns to the state-controlled road.

Following crashes that killed two UF first-year students and injured five more within two months, along with weeks of community outrage, the city and state finally started to change the road.

What makes University Avenue dangerous?

Local politicians, design experts and national city planners point to the road’s speedy design as the culprit behind its danger.

Chris Furlow, the president of Gainesville Citizens for Active Pedestrian, believes University Avenue treats pedestrians as obstacles to cars moving across town as quickly as possible.

A road’s design can prioritize drivers over pedestrians and give drivers cues to slow down, speed up or pay attention, Furlow said. More and wider lanes tell drivers it's okay to go fast. University Avenue’s wide 11-foot lanes give drivers those cues to speed without concern.

A lack of cues to slow down and be aware like raised crosswalks, roundabouts and speed tables — wide, flattop speedbumps — tells drivers they don’t have to pay attention.

Something as subtle as roadside parking and median trees can give drivers unconscious cues to slow down. The more that is blocking drivers’ views, the more likely they are to slow for what they can’t see, Furlow said.

He described high-speed highways like University Avenue as “death by design.”

“They assume there won’t be a lot of pedestrian traffic or people on bikes,” Furlow said. “The state roads are the biggest safety problem right now in Gainesville.”

University Avenue began as a two-lane, pedestrian-friendly road. But by the 1970s, the Florida Department of Transportation began the decadeslong transformation into a four-lane highway.

Mark Barrow, a local historian and founder of Historic Gainesville, has watched University Avenue change since he began his degree at UF in 1953.

“When I got here, University Avenue was lined by big oaks on either side of the street,” said Barrow, who has lived in Gainesville for 68 years. “It was a two-lane road, not a four-laner.”

It was once a dirt road called Alachua Avenue and Liberty Street, Barrow said. The city paved the road after Gainesville was established as the seat of Alachua County in 1854 and renamed the street University Avenue in 1911 after UF was established.

FDOT stripped on-street parking and added lanes throughout the ’70s and ’80s, according to Gainesville Sun archives.

“It was all in the name of progress,” Barrow said. “You’ve got to build, build, build.”

The justification for reconstruction was not unique to Gainesville.

Pedestrian safety wasn’t a priority when University Avenue was expanded, said Victor Dover, one of Gainesville’s former city planners.

“All over America, streets like University Avenue were disfigured in the name of happy motoring and made faster and faster,” he said.

Engineering attitudes focused on cars, businesses and moving quickly, Dover said.

Cities and states wanted wide and fast-moving roads to keep congestion from building up in rush hours, Dover said. These roads were meant to support the economy by getting people to places faster.

Gainesville’s roads host thousands of students in foot traffic from UF. Increasing road widths to ease rush hour left pedestrians exposed for the other 23 hours of the day, he said.

“When a road is too wide, when congestion dies down and you’re off-peak, it becomes a road that is too fast,” he said.

Ignoring the experts

Experts warned about the dangers of University Avenue for decades — but city officials didn’t listen.

The city hired national planners to renovate neighborhoods along the road in the ’80s and ’90s. City planners cautioned the road was dangerous to pedestrians and stunted economic growth.

David Coffey, who served as a city commissioner from 1986 to 1993, was appointed mayor in 1988. During his mayorship, he brought in a city planner, Andrés Duany, to redesign the College Park neighborhood. This neighborhood stretches east from 13th Street to 20th Street and encompasses Midtown and student housing complexes.

Despite being hired to plan a student housing development, Duany took an interest in University Avenue. He saw the road as an obstacle to the neighborhood's growth.

“His observation was, until you do something about the condition on University Avenue, you're never going to be very successful creating a quality place for people along its edge,” Coffey said.

Duany immediately noticed the road was hostile for pedestrians and lacked cues to slow down, Coffey said.

“People will drive as fast as the road feels comfortable driving. And then some,” Coffey said. “The best way to modify that behavior is not by issuing tickets and yelling at people. It is to modify their comfort level.”

Duany recommended on-street parking, which could have shielded pedestrians from traffic, cued drivers to slow down and bolstered economic development, Coffey said.

Allowing University Avenue to act as a highway severely hindered business development in the area, Coffey said.

“The potential of pedestrian activity there is about as high as you'll ever find in a town this size,” he said. “The quality of that space is still so severely compromised by the fact that it really is functioning as a highway.”

Duany’s interest in University Avenue wasn’t in the scope of the plans Gainesville hired him to make. The time and money to rebuild the road, plus the energy to overcome political opposition, were too daunting for the city to take up, Coffey said.

Duany saw the same problems with the road that another city planner would point out 10 years later.

Gainesville hired Victor Dover, a city planner with international firm Dover, Kohl & Partners, to redesign College Park and University Heights neighborhoods for Gainesville in 1999.

“Too wide, too fast. All about cars,” he said about the road. “As for pedestrians, their safety is very much an afterthought.”

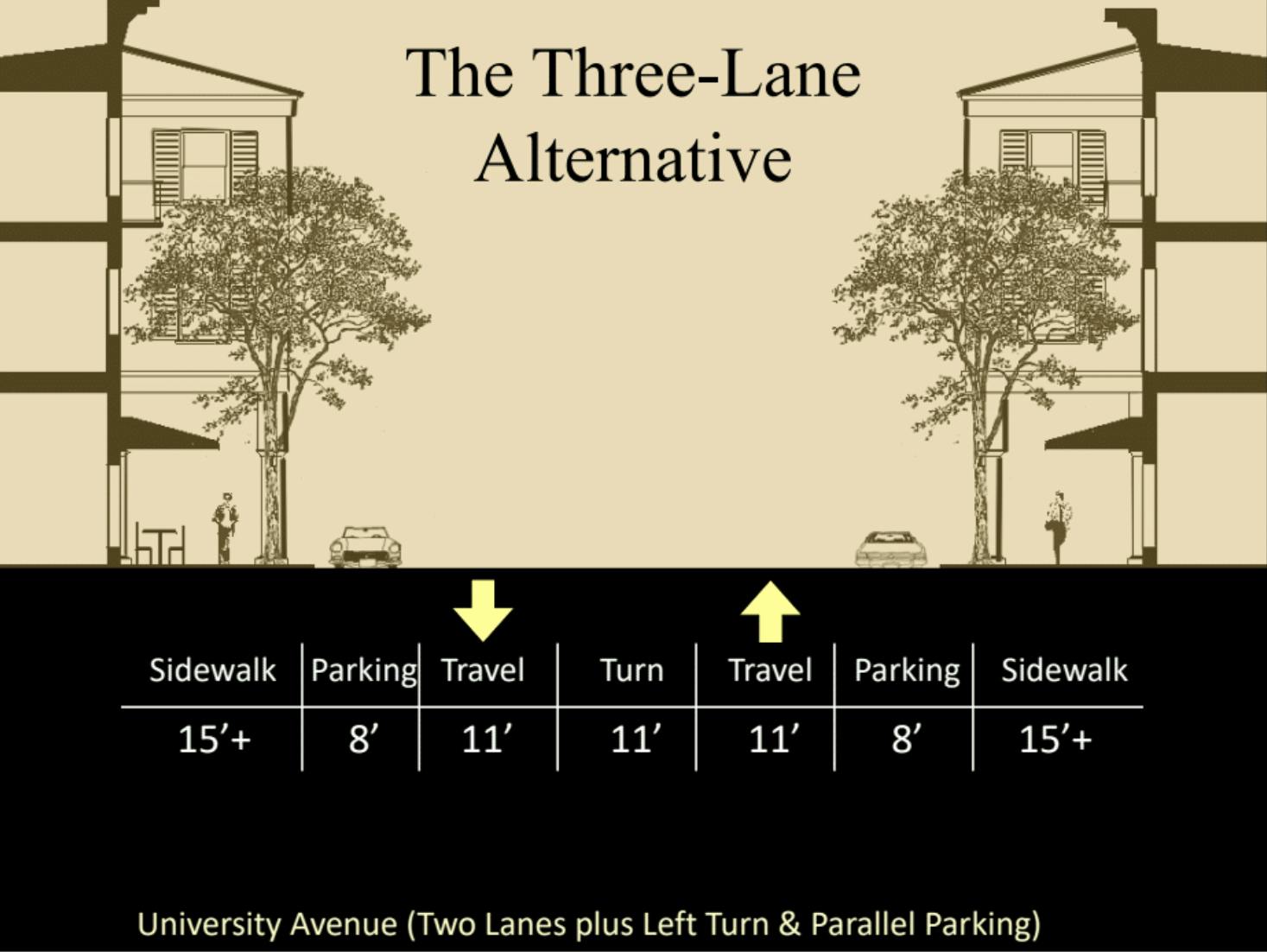

Dover included a University Avenue redesign in his plan that would have cut it to two lanes with a shared turning lane.

The extra room would have been used for bike lanes, pedestrian walkways, shop fronts and trees. One alternative even reinstated slanted, on-street parking.

These images show how Dover, Kohl & Partners planned to protect pedestrians and bolster economic growth on University Avenue. [Photo courtesy of Dover, Kohl & Partners' 1999 presentation for its redesign of College Park and University Heights]

Dover traced the road’s problems back to FDOT, the state agency that owned the road, and left Gainesville city officials relatively powerless in their ability to reform it.

University Avenue, which is part of State Road 26, was controlled by FDOT until the state agency handed over responsibility to Gainesville in February following community outrage over the UF freshmen’s deaths. Gainesville now controls the stretch of University Avenue from 34th Street to 13th Street.

The state agency was responsible for the road’s expansion and designed the road for fast cars. In 2019, FDOT classified University Avenue as a road for drivers going 30 to 45 mph. Since the crashes that killed UF freshmen in December and January, the community has been calling for a speed reduction to 20 mph.

Faster roads make crashes deadlier and more dangerous, according to the European Commission on Mobility and Transportation.

“The state has this overarching regional responsibility to keep things moving for the economy,” Dover said. “The cross-town mobility needs are more important than the close-up experience of life lived in the neighborhood.”

Pegeen Hanrahan said opposition to University Avenue’s redesign also came from a local level. She served terms as Gainesville’s mayor and commissioner from 1996 to 2010 and hired Dover. University Avenue hasn’t changed in Hanrahan’s 54 years as a Gainesville native.

“It's been this big wide expanse of asphalt with relatively narrow sidewalks, not many street trees, not many crossing points,” she said.

Hanrahan saw pedestrians stream to the road since the 1999 plan as students ditched their cars in preference for walking and public transport.

During the early ’90s, RTS annual ridership ranged from 1.3 to 2.9 million people, according to data from Gainesville’s Department of Transportation & Mobility. Ridership climbed before it peaked in 2013 at 10.9 million and dipped to 9.2 million in 2019, according to the data.

Students pushed to have transportation included in tuition fees in 2001. Now that students can ride anywhere with their Gator Card ID, fewer cars are on the road.

More students are living closer to campus, too, Hanrahan said. Several student-housing projects have risen on campus’ borders in recent years, which means more foot traffic on the road.

More than 11 new residential construction plans have been approved for the neighborhood around the intersection of University and 13th Street, according to Gainesville’s project dashboard.

Hanrahan said local business opposition and inertia of political action froze any plans to redesign the road for these pedestrians.

Some University Avenue businesses feared losing customers with slower roads, and some drivers balked at more traffic. Redesigning University Avenue would have cost upwards of $10 million, she estimated.

“There were a lot of people who liked to get from point A to point B as fast as they possibly can and to heck with anyone who gets in their way,” she said.

Those people are the majority of Gainesville citizens, according to Ed Braddy, who served terms as commissioner from 2002 to 2008 and then as mayor from 2013 to 2016.

“There's a big difference between some activists who will show up at a planning charrette in the middle of the week versus the vast majority of people who go to their jobs, work hard — they come home at night and just try to go about their business,” Braddy said.

Braddy opposed many plans for improving University Avenue during his terms, including reducing lanes and creating one-way pairs. This would have made University Avenue a one-way road heading west with a new, parallel one-way road heading east.

He said the “radical” plans weren’t supported by the community but concocted by bureaucratic city planners in Gainesville. Any community support for the changes was cherry-picked by the planners to drown out the silent majority.

Braddy considered city planners to be overreaching what’s necessary.

“It's not enough for some to simply say, ‘Maybe we should reduce the speed limits, and maybe we should improve the bicycle facilities,’” he said. “Instead, it becomes almost anti-automobile hostility. ‘How can we make those who drive more miserable?’”

He sees these improvements as a recipe for more traffic congestion. Fewer lanes won’t keep pedestrians safe, Braddy said. He wants plans that move pedestrians and sidewalks away from the roads and reduce lane capacity.

He thinks this can be achieved by retiming traffic signals and bringing traffic to other east-west roads.

The long struggle

Some Gainesville residents have resisted University Avenue’s expansion since its proposal. Over the years, the Gainesville government and pedestrian advocate groups joined the efforts to make it a safer road. Until this year, all attempts failed.

Local opposition and FDOT inaction have kept University Avenue locked in as a fast-moving road.

The Metropolitan Transportation Planning Organization oversees the urban transportation planning program used to receive state and federal funding for Gainesville’s roads.

The organization releases a list of traffic projects each year to FDOT requesting funding, which ranks projects the city wants the state to fund in order of importance.

While University Avenue projects have been on MTPO’s list of priority projects for decades, FDOT hasn’t complied, said City Commissioner David Arreola, who chaired MTPO from 2020 to 2021.

“For years now, this section of the roadway has been our number one funding priority given to the state of Florida for them to fund. And they've done nothing with it,” Arreola said.

MTPO requested funding for projects expanding the road, updating infrastructure and making the road safer for pedestrians for decades. Following a 2015 study of University Avenue, pedestrian-related solutions have remained a top priority, according to MTPO priority lists from 1995 through 2020.

The study proposed more sidewalks, bike lanes, pedestrian crossings, redesigned intersections for pedestrians, improved bus stops and added raised medians. None of the projects were funded by FDOT, Arreola said.

FDOT spokesperson Troy Roberts could not immediately comment on these specific projects.

“FDOT funds projects based on the priorities of the MTPO,” he wrote in an email.

Arreola believes FDOT sees the road in a different way than the city.

“We believe that it's about moving people, not about moving cars,” he said. “We don't think that local roadways should be built like interstate highways.”

A safer, slower future ahead

Over the decades, sentiments about Gainesville city design have changed.

States and cities became friendlier to ideas that seemed too difficult 20 years ago, such as widening sidewalks and repurposing lanes, city planner Dover said.

University Avenue hasn't updated as fast as Gainesville’s other roads — the asphalt has been laid, and it can take decades for changes to be made again.

“Unlike the software in your computer or the programs on your streaming service, the built environment changes very slowly,” Dover said. “It takes a long time to build things, have them wear out and get around to have them being replaced.”

Roads are rebuilt during once-in-two-decade repavings or subterranean cable replacements, Dover said.

“Twenty years is the blink of the eye in city-planning times,” he said. “For the parents of those kids, it seems too late.”

This article has been updated to reflect that Pegeen Hanrahan is 54 and served on the Gainesville City Commission from 1996 to 2010. The Alligator previously reported otherwise.

Contact Lianna Hubbard at lhubbard@alligator.org. Follow her on Twitter @HubbardLianna.

Lianna Hubbard is a reporter for The Alligator’s Investigative Team. The UF women’s study major began as a freelance reporter three years ago. She founded her community college’s award-winning newspaper before beginning at The Independent Florida Alligator. See an issue in your community or a story at UF? Send tips to her Twitter.

![<p>A photographed undated postcard of University Avenue before the 1970s and 1980s renovations that eliminated on-street parking along the road. [Photo courtesy of the Matheson History Museum]</p>](https://snworksceo.imgix.net/ufa/79090ab0-6246-4dc4-bdff-98571c7d4f5c.sized-1000x1000.jpg?w=1000)