With his lip lifted up to the side and a bright twinkle in his eye, Neil Butler Sr. ran around Downtown Gainesville in a fresh, white nurse suit. Despite always being in a rush to get somewhere, he stopped to talk to anyone who said hello.

He was a people person.

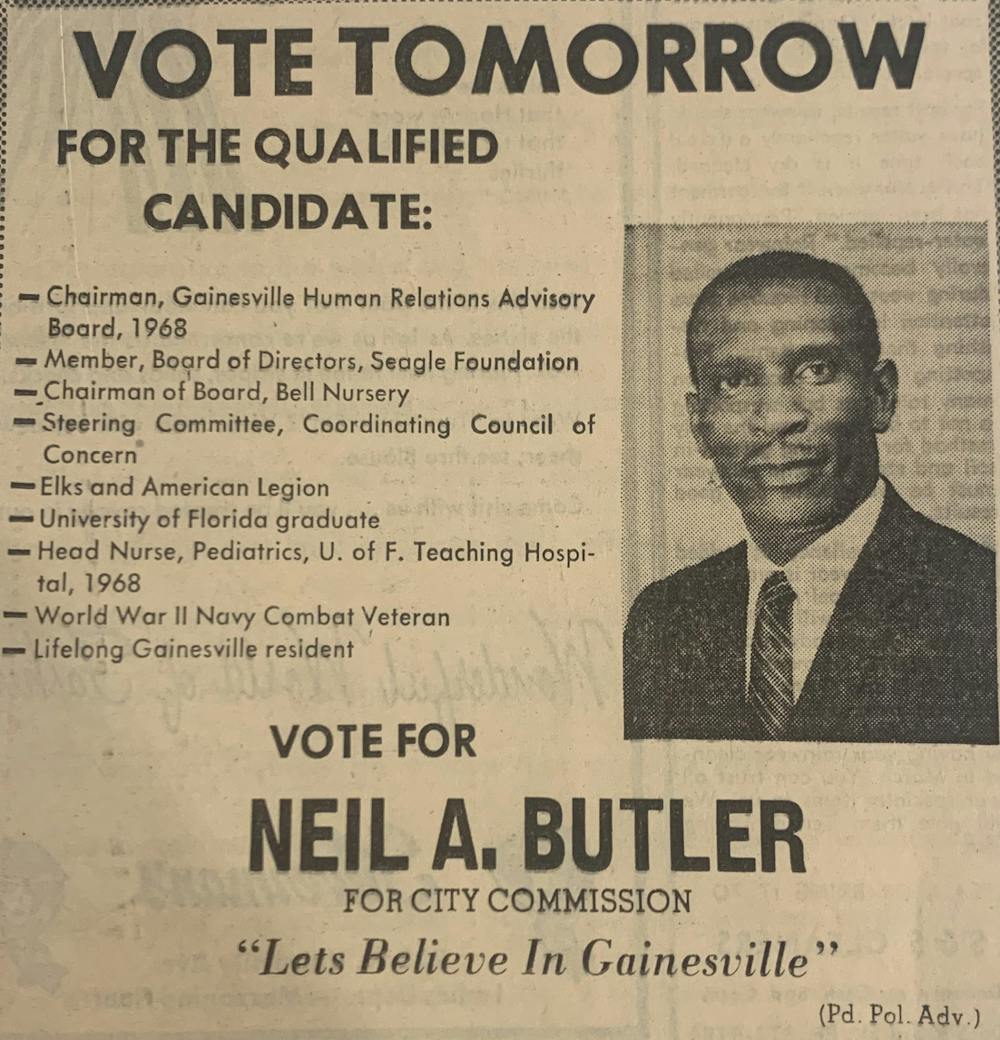

Butler was elected into the city commission in 1969, becoming the first Black man elected to the body since Reconstruction, an era marked by post Civil War opportunities. Later, in 1971, he became the first Black Mayor to hold that office in 100 years. However, he wanted to be remembered for who he was rather than being the first.

Butler sent shockwaves throughout the city when he won the City Commission election. His daughter, Annette Butler-Johnson, 68, was in high school at the time and remembers feeling immense pride for her father.

“When he was elected, the city of Gainesville was 80% white,” Butler-Johnson said.

“That's a major accomplishment for a Black man to come in and win an election with an 80% white community.”

Butler was born in Orange Heights, Florida, in 1928 and was raised during a time when segregation dominated society. He had to use the bathroom in the basement of the courthouse because Black people were not allowed to use public facilities.

He was a World War II combat veteran and spent time on Okinawa Island. After his service, he studied at Morris Brown College in Atlanta, Georgia.

Butler was a strong believer in education and reinforced that belief in his children. When Butler-Johnson and her nine siblings asked him what a word meant, he encouraged them to use their dictionaries.

“He would say ‘Get your dictionary, look it up and you will remember it more. If you look it up and read it, you’re more prone to remember it than if I just tell you what it is,’” Butler-Johnson said.

Butler pushed his children to stand up for themselves and work hard for the things they were passionate about. One of his sons, Danny Butler, built a car with his father for a Soap Box Derby competition when he was a young Boy Scout.

The car needed a sponsor, so Butler took Danny to the Sun Bank to pitch the car. Danny, now 61 years old, remembers the experience as one of his fondest memories of his father.

“That's the kind of person he was,” Danny said. “He wouldn't go do it for you. He would want you to do it for yourself and you would learn from it.”

Coincidentally, Danny won a mock election at his school at the same time his father won the 1969 city commission election.

While working two full-time jobs, Neil Butler Sr. attended a practical nursing class, which was operated by the Alachua County Board of Education, in 1964. A year later, he enrolled in UF’s College of Nursing.

He faced probation at one point in his studies, but by the time he graduated he made the dean’s list. He earned a bachelor’s and a master's degree in nursing.

He was the only Black male student in the Graduate School of Nursing at UF, according to a 1971 edition of Ebony Magazine. He was also the first African American male to graduate from the college, Danny said.

Butler served as a city commissioner until 1971 when he became mayor. During this time, he was surrounded by controversy over allegations that Butler committed a felony.

Butler pleaded guilty to mail embezzlement of $9 while living in Atlanta in 1959. The conviction placed Butler on probation for two years, and he lost his right to hold office.

In 1972, The Sun published an article about the charge.

The day after publishing, Butler resigned from his position as Mayor. However, the Florida Board of Pardons restored his rights on Dec. 16, 1971.

Butler grew up in church, and his community at Mt. Olive A.M.E. Church tried to look past the incident. Vivian Filer, 83, the CEO of the Cotton Club Museum and Cultural Center and a now-retired professor of nursing, was a member of the church at the time of Butler’s election and described their community as close-knit. Everybody knew each other.

Filer believes the crime was either made up or embellished. During this period in American history, crimes were fabricated for the purpose of targeting Black people.

“That's not the Neil we know,” Filer said. “We knew the real Neil so we knew that wouldn't have been something that he would do.”

Filer recalls how the church celebrated Butler’s election for days. He was its pride and joy.

“We talked about it. We spread the news. We congratulated him. He was constant in our conversation,” Filer said. “To me, he knew a lot about politics, about life, about laws, about whatever he put his hand to, he perfected and that to me was inspirational.”

Butler faced many instances of discrimination during his terms as mayor and city commissioner.

Butler-Johnson was in constant fear for her father’s life. Martin Luther King Jr. was killed when she was in elementary school. The fear her father could be murdered in the same way was always in the back of her mind.

“Him being in that position, there was always a chance that somebody might try to hurt him or to do something,” she said.

Butler received death threats that his home would be shot up, Danny said. His father would sleep on the floor of their home at night to guard the house.

“He knew going into it that he would be facing adversity, but it was something that he felt had to be done and that he needed to do because there were underrepresented people,” Danny said, “And he felt he could do something to change that.”

Butler’s niece Ayesha Solomon, 42, recalls being told by one of his children that they feared he would be killed by the white men. Solomon doesn’t have memories with her uncle but learned about him through family stories.

“My relatives shared with me that he was a man who lived a very purposeful life,” she said. “Uncle Neil was all about helping all people.”

Through research, Solomon discovered details about Butler’s legacy and was incredibly impressed by his return to Gainesville politics after the embezzlement controversy.

In 1972, Butler was declared eligible for the March city commission race. Forty-five days after Butler resigned, he was elected back onto the city commission and carried 56% of the vote, according to an article by The Sun. He served as a City Commissioner until 1974 when he was appointed to his second term as Mayor-Commissioner.

Butler tackled many issues during his time as Mayor and City Commissioner, including inequality, utility rates and city structure. He paved dirt roads in Black neighborhoods. He also initiated a minority recruiting program that increased the number of Black firefighters and police officers.

Butler considered continuing his career into the Florida Legislature. The Hatch Political Activities Act prohibited federal employees from participating in political campaigns. Butler’s job at the Gainesville VA Medical Center made him a federal employee.

To this day, Filer attends Mt. Olive A.M.E. Church and greets Butler’s children. Filer remembers Butler as an inspiration, someone who paved the way and changed her world.

“I think people like Neil and others doing that kind of work certainly was inspirational to all of us, who were in the field trying to make a difference and facing all of the harassment and everything that was going on,” Filer said.

Butler-Johnson and Solomon followed Butler’s legacy through different fields. Butler-Johnson became a licensed practical nurse. Butler told her to continue her education to become a registered nurse but she decided against the idea.

“I worked as an LPN at the VA until my pay scale couldn’t go up any higher so I still had to work. Why not go back to school?” Butler-Johnson said. “And I thought about it and I said ‘Lord if I’d just listened to my dad, I’d be way beyond this point right now.’”

Solomon became the first Black property appraiser for Alachua County and first Black female property appraiser in Florida.

“If Neil Butler was here today, I think his advice to me would be to focus on your purpose,” Solomon said. “My primary objective is to be great at serving the community and if I so happen to make history then so it is.”

Solomon, Butler-Johnson and Danny Butler all passed down their stories to their children. They hope that he won’t be forgotten.

“It's required to know that that’s your lineage and that’s your history,” Danny said, “And that someone was bold enough to step out on those ledges in times when it wasn't very easy to do so.”

Butler-Johnson asked the children at her church about impactful Black leaders. They all knew who Martin Luther King Jr. was but when she asked them about Butler, the room grew silent.

“That’s so important because if we don't pass it onto our children and they pass it onto their children, he’ll get lost in the limelight,” Butler-Johnson said. “I think a lot of times he has gotten lost in the limelight.”

Butler-Johnson was disheartened to hear Gainesville children were unaware of Butler’s legacy but felt hope knowing that one of Butler’s grandchildren would be giving a presentation Feb. 27 on his impact at Agape Faith Center Ministries.

“I want to make sure that they know who he was, and how instrumental he was in doing so much for the city of Gainesville and the community,” Butler-Johnson said.

Solomon believes that Gainesville does not do enough to celebrate his legacy. She feels that there should be a street or building named after him.

“I wish that Gainesville did a better job of acknowledging the strides that we've made in Black history by reminding the community of great leaders who served before us,” she said. “What does that really mean if you don't celebrate it, acknowledge it, or honor it?”

Despite Gainesville’s lack of commemoration for Butler’s legacy, he lives on in the community as someone who truly changed the city. He wanted to be remembered as a strong father, accomplished nurse and inclusive leader.

Butler passed away in 1992 at the age of 64. He died of a heart attack while attending a friend’s wedding anniversary. His legacy and impact went beyond his political achievements. Butler touched the lives of everyone he met.

“Sometimes one wonders how you survive when you’re faced with those obstacles, but you never give up,” Butler said in an archived article by The Sun. “Little by little I got more resilient by facing those troubles, and that strengthened me in the long run.”

Contact Melanie at mpena@alligator.org or follow her on Twitter at @MelanieBombino_.

Melanie Peña is a second-year business and journalism major. When she's not designing a graphic or writing an article, she's probably making jewelry or exploring coffee shops in Gainesville.